The name “Anthony Standifer” is not one that carries much meaning for the vast majority of Michigan fans.

Perhaps those who watch a lot of college football in general recognize Mr. Standifer as a middling defensive back prospect who played one season for the Ole Miss Rebels before transferring to Eastern Illinois and playing out his career in obscurity. But Michigan? What’s Anthony Standifer got to do with the Michigan Wolverines?

Nothing, really. Indeed, “nothing” might even pass for a satisfactory answer to some. For those who have studied Michigan Football for far too long, however, watching with intense frustration almost every year as some strange culimination of minor butterfly effects conspires to rob the Wolverines of glory, Mr. Standifer’s connection with the program is clear. And profound.

You see, Anthony Standifer grew up in the far south suburbs of Chicago, in a town called Crete on the Cook County-Will County line. There, he was a star player for his high school football team, the Crete-Monee Warriors—helping them to an undefeated regular season and 10-1 finish in his senior year. He caught plenty of attention from college scouts as a cornerback prospect, drawing a three-star ranking and earning offers from Power-5 programs like Iowa, Pittsburgh, even Notre Dame. And Michigan.

Now, Standifer was a star on the Warriors football team and a nice college prospect; he wasn’t the star. Standifer’s best friend, a year behind him at Crete-Monee, was a player the prep scouts generally agreed was the top wide receiver prospect in the country. That player, Laquon Treadwell, would receive scholarship offers from substantially every major college football program and finish his recruiting cycle as the #1-ranked WR prospect and #5 overall recruit on Rivals.com. In 2016, the Minnesota Vikings would select him in the first round of the NFL entry draft. Five years earlier, in 2011, Michigan wanted Anthony Standifer to play on their defense. But they really wanted Laquon Treadwell to play wide receiver.

No defensive back prospect anywhere in the country could be seriously faulted for declining a Michigan offer in early 2011, when Standifer received his. The 2010 Michigan secondary had been an epic dumpster fire, and though Rich Rod and his failed defensive staff were gone his replacement did not inspire a ton of confidence. Yet Standifer was undeterred, and committed to Brady Hoke and the Wolverines in June 2011.

His friend and teammate’s verbal pledge to the Wolverines did not hurt their standing with Treadwell; Michigan was widely reported to as the leader for his services both before and during Standifer’s commitment, with college football recruitniks penciling Treadwell in for Michigan on various “way too early” signing day projections.

His friend and teammate’s verbal pledge to the Wolverines did not hurt their standing with Treadwell; Michigan was widely reported to as the leader for his services both before and during Standifer’s commitment, with college football recruitniks penciling Treadwell in for Michigan on various “way too early” signing day projections.

So it was quite the surprise when news broke in December 2011 that Standifer had withdrawn his commitment from Michigan. Two months later, Standifer faxed his signed letter of intent to Oxford, Mississippi, home of the 2-11 Ole Miss Rebels.

Missing out on Anthony Standifer was a minor setback for Michigan, who nonetheless signed the nation’s #6-ranked recruiting class that season and has consistently fielded quality cornerbacks ever since GMat returned to the Big House. Michigan remained the leader for Treadwell, and hopeful fans eagerly anticipated a five-star haul at QB (Shane Morris 😐), running back (Derrick Green 😞), and wide receiver for signing day 2013.

But with his boy in Oxford rather than A2, Treadwell’s interest in the Wolverines slowly waned over the ensuing year. Finally, on December 16, 2012, Treadwell disclosed that he’d eliminated Michigan from consideration in his recruitment. Six weeks later, Treadwell too would commit to the Ole Miss Rebels.

But with his boy in Oxford rather than A2, Treadwell’s interest in the Wolverines slowly waned over the ensuing year. Finally, on December 16, 2012, Treadwell disclosed that he’d eliminated Michigan from consideration in his recruitment. Six weeks later, Treadwell too would commit to the Ole Miss Rebels.

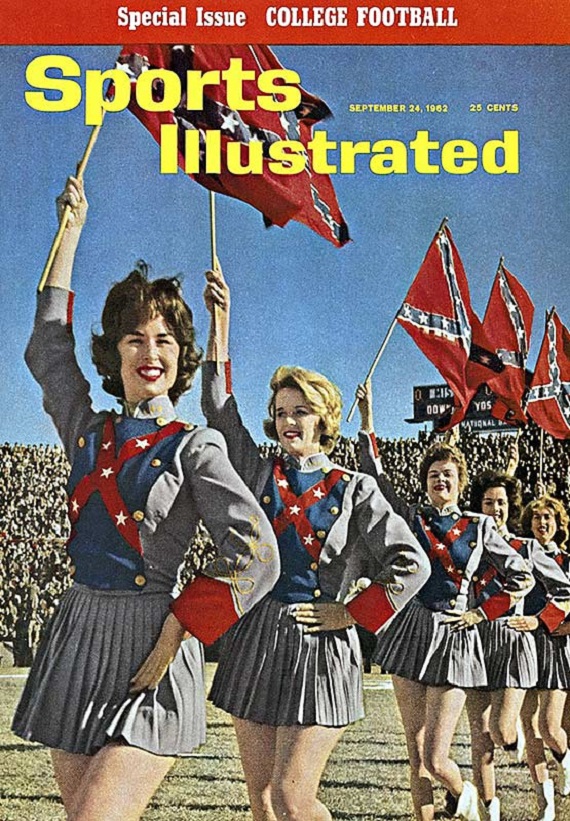

Now, for Michigan to lose out on football commits to programs like Alabama and Ohio State is certainly understandable from one side of the equation, and losing out on recruits to Stanford or Northwestern (ah, okay, M doesn’t lose out on recruits to Northwestern) is understandable from another. But losing recruits to a longstanding SEC punching bag with a mediocre academic reputation, known mostly for unapologetic racism, did not add up. So Laquon had to add it up for us, which he did by tweeting out photos from Oxford recruiting visit with large stacks of cash and plenty of Rebel “hostesses.”

Being the bullshit, doormat program that they are, from Ole Miss’ perspective the sanctions were probably worth it. After finishing 2-10 the season before Freeze arrived, Ole Miss went 34-18 over the next four seasons—including a 10-3 season in 2015 that included a win over top-ranked Alabama and a top-10 finish in the AP poll. Those 34 wins may be vacated, but vacating Ole Miss’ wins does not erase the pain those 34 teams that lost those games endure any more than sanctioning Hugh Freeze or banning Ole Miss from bowl contention puts Anthony Standifer and Laquon Treadwell back on Michigan ‘s roster. There truly is no justice with NCAA investigations, only pain. Except, perhaps, when karma gets involved.

The top overall recruit in the 2016 class, defensive end Rashan Gary, signed with Michigan after a protracted recruiting battle with Clemson that reportedly went down to the wire. Clemson did sign the #2 player, defensive tackle Dexter Lawrence. But Ole Miss, despite receiving its first NCAA notice of allegations just two weeks earlier, signed both the #3 and #4 ranked players in 2016: offensive tackle Greg Little, and quarterback Shea Patterson.

Having already played two seasons for Ole Miss, the two-year post-season ban would effectively preclude Patterson from playing for any kind championship or bowl appearance throughout the rest of his Ole Miss career. So Patterson, along with at least five teammates, decided to transfer.

Ordinarily, undergraduate student-athletes who transfer from one FBS program to another are ineligible for one year from the date of transfer. But Patterson is a major NFL prospect, projected as a first-round selection for 2019. So his basic menu of options wasn’t terrific: (1) stay at Ole Miss and get his ass kicked on a depleted, sanctioned team for a year, then go pro; (2) transfer to an FBS program, sit out one year, and then either play another 1-2 years of college ball or go pro with a likely reduced draft grade; or (3) transfer to an FCS program and play immediately, but receive (probably) inferior coaching and minimal exposure.

Patterson and the Rebel 6, who claimed Ole Miss tricked them into enrolling by downplaying the NCAA allegations and lying about the potential sanctions, believed they could make that showing. So in December 2017, Patterson and his teammates began touring other prominent FBS programs, intending on transferring and seeking waivers for immediate eligibility. Michigan hosted three of those players—Patterson, top safety Deontay Anderson, and wide receiver Van Jefferson—and likely would have signed all three of them had they the necessary academic qualifications. Anderson and Jefferson did not—but Patterson did, and started classes in Ann Arbor in January 2018.

Now, the EGD has always found Patterson’s claim (that he was deceived into enrolling at Ole Miss) a bit dubious. Actually, a lot dubious. As noted above, the rampant cheating and improper benefits scandals at Ole Miss were an open secret for years before the NCAA got involved, and if it was obvious to college football fans then it should have been even more obvious to someone like Patterson—who played at IMG Academy (a Florida high school that recruits and provides advanced coaching and guidance for top athletes in a number of sports), visited the schools both officially and unofficially, and had access to qualified advisors--including his own brother, who was on the Ole Miss staff. That a two-year post-season ban—a fairly common sanction leveled for these types of infractions—could be (indeed, likely would be) imposed for Freeze’s flagrant clownshow of NCAA violations could hardly have been surprising.

Ole Miss didn't buy it either, and formally objected to Patterson’s waiver request—setting up a showdown between Patterson and Ole Miss in some NCAA adjudicative tribunal. But that showdown never happened.

Ole Miss didn't buy it either, and formally objected to Patterson’s waiver request—setting up a showdown between Patterson and Ole Miss in some NCAA adjudicative tribunal. But that showdown never happened.

M will probably only have Patterson for one season, two max. But if he can post another 151.5 QB rating over 12+ games at Michigan, it’ll go a long way toward paying off that Laquon Treadwell-sized karmic debt that Mississippi owes the Blue.

And Patterson got a good start on this in spring camp, reportedly impressing his new coaches enough that he led for the starting job by the end of the session. He solidified that lead enough in fall camp that the notoriously tight-lipped Harbaugh had already named him the starter for Michigan’s opener by the middle of August.

Since there was no spring game this year, we have yet to see Patterson run a play in a winged helmet. But Patterson’s seven 2017 games at Ole Miss should provide a fairly good preview of what we can expect.

The first thing you’ll notice about Patterson is the athleticism to extend plays. He shows escapability in the pocket, can scramble some, and throws accurately on the run. Denard Robinson he is not; he’s closer to Tate Forcier—though with a better arm and less of the insanity. You’d have to go further back, though, for what I’d consider his best M comp: a guy who wore No. 7.

Patterson is an outstanding short game QB. He’s got a quick release, makes fast, accurate RPO reads and gets a catchable ball to the edge accurately and with zip. His deep ball—like practically any college QB—is inconsistent, but he has plenty of arm strength and excels at throwing open big receivers.

All in all though, Patterson looks like an outstanding pickup for Harbaugh and the Wolverine offense. He’s experienced, has great physical tools, and he’s produced on the field.

How well Patterson ultimately does at Michigan appears likely to turn on two key points. First, how quickly and effectively will he adjust to Harbaugh’s offense? The scheme Patterson ran at Ole Miss used predominately 10 (one running back, no TEs) and 11 (one running back, one TE) personnel, and most of their plays were RPOs (“run-pass options”) involving almost exclusively zone blocking paired with quick slants, pop passes, and deep routes. It was Patterson’s job to catch the shotgun snap, mesh with a running back while reading a key defender, and correctly decide whether to complete the handoff (if the key dropped into coverage) or pull the ball back and throw (if the key committed to the run).

Michigan, by contrast, prefers heavier personnel groupings—using an array of fullbacks, H-backs, and tight ends on substantially every play. And though Michigan is reportedly incorporating more RPO concepts into its offense, the M running game is almost certain to remain heavily gap-based after last season’s disastrous experiment with zone schemes. Patterson will need to show he can be as effective in managing Michigan’s gap-based running schemes in heavy personnel groups as he was with zone concepts in Ole Miss’ spread offense.

How well Patterson ultimately does at Michigan appears likely to turn on two key points. First, how quickly and effectively will he adjust to Harbaugh’s offense? The scheme Patterson ran at Ole Miss used predominately 10 (one running back, no TEs) and 11 (one running back, one TE) personnel, and most of their plays were RPOs (“run-pass options”) involving almost exclusively zone blocking paired with quick slants, pop passes, and deep routes. It was Patterson’s job to catch the shotgun snap, mesh with a running back while reading a key defender, and correctly decide whether to complete the handoff (if the key dropped into coverage) or pull the ball back and throw (if the key committed to the run).

Michigan, by contrast, prefers heavier personnel groupings—using an array of fullbacks, H-backs, and tight ends on substantially every play. And though Michigan is reportedly incorporating more RPO concepts into its offense, the M running game is almost certain to remain heavily gap-based after last season’s disastrous experiment with zone schemes. Patterson will need to show he can be as effective in managing Michigan’s gap-based running schemes in heavy personnel groups as he was with zone concepts in Ole Miss’ spread offense.

The second key point in Patterson’s success is largely outside his control. Michigan’s offensive line struggled terribly in pass protection last season, with inexperienced new starters struggling to pick up twists, stunts, and blitzes. Free rushers claimed Wilton Speight in week four, landed Brandon Peters in the concussion protocol against Wisconsin, and forced Harbaugh to start John O’Korn in key games against Michigan State, Penn State, and OSU. Patterson’s escapability should certainly help him, no doubt. But to produce the kind of numbers he’s capable of, he'll absolutely need better pass protection than what M produced last year. If he gets it, and the EGD thinks he will, then watch out.

Patterson’s primary backup in 2018 will be redshirt sophomore Brandon Peters, who started five games in 2017 and did not exactly light the Big Ten on fire, posting just a 113.6 efficiency rating on 6.2 yards per attempt. He was dreadful in the Outback Bowl against South Carolina, completing just 20/44 passes for 186 yards and tossing two interceptions. But it’s important to remember he did that as just a redshirt freshman. As a cerebral QB in the mold of a Todd Collins or Brian Greise, Peters will reach his ceiling only after mastering the nuances of the offense and developing advanced technique and muscle memory. He wasn’t ready in 2017; he may or may not be ready in 2018. But Perters can be a solid backup to Patterson, a superior athlete much closer to his maximum potential. Hopefully that’s all M will need.

Milton’s a Pahokee kid with a rocket launcher for an arm, and will likely see time this season only because of a new NCAA rule change that allows a player to compete in up to four games without burning his redshirt. More on him next year then. This year belongs to Shea Patterson.

Bottom Line: Quarterbacks

Probable starter: Shea Patterson

Key backups: Brandon Peters, Dylan McCaffrey

Other possible options: Joe Milton

Position grade: A-

I had estimated this position group about a B or B+ until I watched Patterson’s film. He’s a legit player and the only serious question is how well (and how quickly) he’ll mesh with his new teammates and Harbaugh’s schemes. Then M has an experienced backup in Peters and developmental talent for the future in McCaffrey and Milton. Pretty damn good.

No comments:

Post a Comment